amyehodge.github.io

Hands-on Introduction to the Shell, Part 2

Now that you know how to navigate the shell, we will move onto learning how to count and mine data using a few of the standard shell commands. While these commands are unlikely to revolutionize your work by themselves, they’re very versatile and will add to your foundation for working in the shell and for learning to code.

Counting and sorting

We will begin by counting the contents of files using the Unix shell. We can use the Unix shell to quickly generate counts from across files, something that is tricky to achieve using the graphical user interfaces of standard office suites.

Let’s start by navigating to the directory that contains our data using the

cd command:

$ cd shell-lesson

Remember, if at any time you are not sure where you are in your directory structure,

use the pwd command to find out:

$ pwd

Output:

/Users/amyhodge/Desktop/shell-lesson

And let’s just check what files are in the directory and how large they

are with ls -l:

$ ls -l

Output:

total 283792

-rw-r--r--@ 1 amyhodge staff 3.6M Jan 31 16:47 2014-01-31_JA-africa.tsv

-rw-r--r--@ 1 amyhodge staff 7.4M Jan 31 16:47 2014-01-31_JA-america.tsv

-rw-rw-r--@ 1 amyhodge staff 125M Jun 10 2015 2014-01_JA.tsv

-rw-r--r--@ 1 amyhodge staff 1.4M Jan 31 16:47 2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv

-rw-r--r--@ 1 amyhodge staff 582K Feb 1 23:15 33504-0.txt

-rw-r--r--@ 1 amyhodge staff 598K Jan 31 16:47 gulliver.txt

drwxr-xr-x 2 amyhodge staff 68B Jul 31 11:43 backup/

In this episode we’ll focus on the dataset 2014-01_JA.tsv, that contains

journal article metadata, and the three .tsv files derived from the original

dataset. Each of these three .tsv files includes all data where a keyword such

as africa or america appears in the ‘Title’ field of 2014-01_JA.tsv.

Tip: CSV and TSV Files

CSV (Comma-separated values) is a common plain text format for storing tabular data, where each record occupies one line and the values are separated by commas. TSV (Tab-separated values) is just the same except that values are separated by tabs rather than commas. Confusingly, CSV is sometimes used to refer to both CSV, TSV and variations of them. The simplicity of the formats make them great for exchange and archiving. They are not bound to a specific program (unlike Excel files, say, there is no

CSVprogram, just lots and lots of programs that support the format, including Excel by the way), and you wouldn’t have any problems opening a 40 year old file today if you came across one.

wc is the “word count” command: it counts the number of lines, words, bytes

and characters in files. Since we love the wildcard operator, let’s run the command

wc *.tsv to get counts for all the .tsv files in the current directory

(it takes a little time to complete):

$ wc *.tsv

Output:

13712 511261 3773660 2014-01-31_JA-africa.tsv

27392 1049601 7731914 2014-01-31_JA-america.tsv

507732 17606310 131122144 2014-01_JA.tsv

5375 196999 1453418 2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv

554211 19364171 144081136 total

The first three columns contains the number of lines, words, and bytes (to show number characters you have to use a flag).

If we only have a handful of files to compare, it might be faster or more convenient to just check with Microsoft Excel, OpenRefine or your favorite text editor, but when we have tens, hundreds or thousands of documents, the Unix shell has a clear speed advantage. But the real power of the shell comes from being able to combine commands and automate tasks. We will touch upon this slightly.

For now, we’ll see how we can build a simple pipeline to find the shortest file

in terms of number of lines. We start by adding the -l flag to get only the

number of lines, not the number of words and bytes:

$ wc -l *.tsv

Output:

13712 2014-01-31_JA-africa.tsv

27392 2014-01-31_JA-america.tsv

507732 2014-01_JA.tsv

5375 2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv

554211 total

The wc command itself doesn’t have a flag to sort the output, but as we’ll

see, we can combine three different shell commands to get what we want.

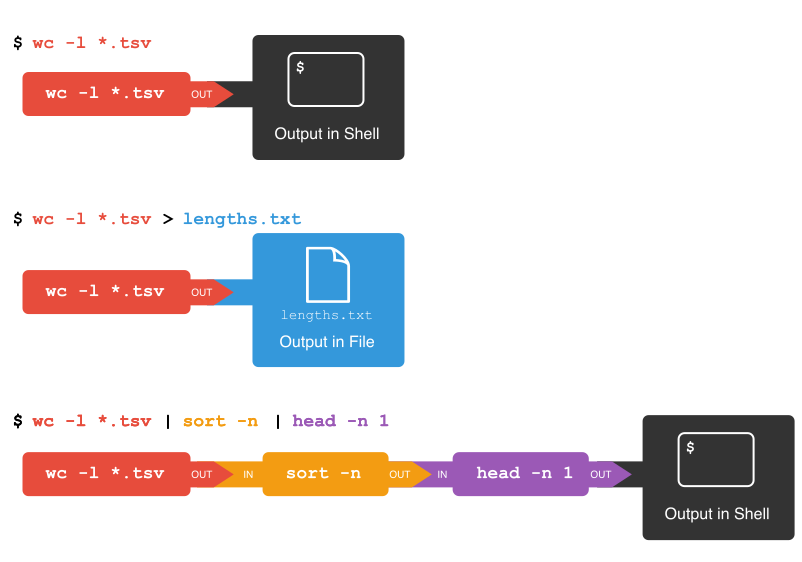

First, we have the wc -l *.tsv command. We will save the output from this

command in a new file. To do that, we redirect the output from the command

to a file using the ‘greater than’ sign > (or right angle bracket), like so:

$ wc -l *.tsv > lengths.txt

There’s no output now since the output went into the file lengths.txt, but

we can check that the output ended up in the file using cat or less

(or Notepad or any text editor).

$ cat lengths.txt

Output:

13712 2014-01-31_JA-africa.tsv

27392 2014-01-31_JA-america.tsv

507732 2014-01_JA.tsv

5375 2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv

554211 total

Next, there is the sort command. We’ll use the -n flag to specify that we

want numerical sorting, not lexical sorting, we output the results into

yet another file, and we use cat to check the results:

$ sort -n lengths.txt > sorted-lengths.txt

$ cat sorted-lengths.txt

Output:

5375 2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv

13712 2014-01-31_JA-africa.tsv

27392 2014-01-31_JA-america.tsv

507732 2014-01_JA.tsv

554211 total

Finally we have our old friend head, that we can use to get the first line

of the sorted-lengths.txt:

$ head -n 1 sorted-lengths.txt

Output:

5375 2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv

But we’re really just interested in the end result, not the intermediate

results now stored in lengths.txt and sorted-lengths.txt. What if we could

send the results from the first command (wc -l *.tsv) directly to the next

command (sort -n) and then the output from that command to head -n 1?

Luckily we can, using a concept called pipes. On the command line, you make a

pipe with the vertical bar character |. Let’s try with one pipe first:

$ wc -l *.tsv | sort -n

Output:

5375 2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv

13712 2014-01-31_JA-africa.tsv

27392 2014-01-31_JA-america.tsv

507732 2014-01_JA.tsv

554211 total

Notice that this is exactly the same output that ended up in our sorted-lengths.txt

earlier. Let’s add another pipe:

$ wc -l *.tsv | sort -n | head -n 1

Output:

5375 2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv

It can take some time to fully grasp pipes and use them efficiently, but it’s a very powerful concept that you will find not only in the shell, but also in most programming languages.

Tip: Pipes and Filters

This simple idea is why Unix has been so successful. Instead of creating enormous programs that try to do many different things, Unix programmers focus on creating lots of simple tools that each do one job well, and that work well with each other. This programming model is called “pipes and filters”. We’ve already seen pipes; a filter is a program like

wcorsortthat transforms a stream of input into a stream of output. Almost all of the standard Unix tools can work this way: unless told to do otherwise, they read from standard input, do something with what they’ve read, and write to standard output.The key is that any program that reads lines of text from standard input and writes lines of text to standard output can be combined with every other program that behaves this way as well. You can and should write your programs this way so that you and other people can put those programs into pipes to multiply their power.

Exercise 9: Adding another pipe

We have our

wc -l *.tsv | sort -n | head -n 1pipeline. What would happen if you piped this intocat? Try it!

Exercise 9 Solution

Exercise 10 : Count, sort, and print

Let’s say you have a directory containing over 100

csvfiles. How would you count the number of words in each file, sort this list, and then output the 10 files with the most words (Hint: Useman wcto check for flags you can use with this command and to verify their behaviors)?

Exercise 10 Solution

Exercise 11: Counting number of files, part I

Let’s make a different pipeline. You want to find out how many files and directories there are in the current directory. Try to see if you can pipe the output from

lsintowcto find the answer, or something close to the answer.

Exercise 11 Solution

Exercise 12: Writing to files

The

datecommand outputs the current date and time. Write the current date and time to a new file calledlogfile.txt. Check the contents of the file.

Exercise 12 Solution

Exercise 13: Appending to a file

While

>writes to a file,>>appends something to a file. Try to append the current date and time to the filelogfile.txtwithout overwriting the previous date and time.

Exercise 13 Solution

Mining or searching

Searching for something in one or more files is something we’ll often need to do,

so let’s introduce a command for doing that: grep (short for global regular

expression print). This command supports regular expressions and

is therefore only limited by your imagination, the shape of your data, and - when

working with thousands or millions of files - the processing power at your disposal.

To begin using grep, first navigate to the shell-lesson directory if not already

there. Then create a new directory “results”:

$ mkdir results

Now let’s try our first search:

$ grep 1999 *.tsv

Remember that the shell will expand *.tsv to a list of all the .tsv files in the

directory. grep will then search these for instances of the string “1999” and

print the matching lines.

Tip: Strings

A string is a sequence of characters, or “a piece of text”.

Press the up arrow once in order to cycle back to your most recent action.

Change grep 1999 *.tsv to grep -c 1999 *.tsv by using the arrow keys and hit enter. The -c flag changes the command so that instead of returning the matching lines, it counts them and displays the number found after each file name.

$ grep -c 1999 *.tsv

Output:

2014-01-31_JA-africa.tsv:804

2014-01-31_JA-america.tsv:1478

2014-01_JA.tsv:28767

2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv:284

If you look at the output from the previous grep 1999 *.tsv command, you can see that 1999 is typically found in the date field for each journal article.

Now try this search:

$ grep -c revolution *.tsv

Output:

2014-01-31_JA-africa.tsv:20

2014-01-31_JA-america.tsv:34

2014-01_JA.tsv:867

2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv:9

We got back the counts of the instances of the string revolution within the files.

Now, amend the above command to the below and observe how the output is different:

$ grep -ci revolution *.tsv

Output:

2014-01-31_JA-africa.tsv:118

2014-01-31_JA-america.tsv:1018

2014-01_JA.tsv:9327

2014-02-02_JA-britain.tsv:122

The -i flag makes the command case

insensitive, so that it now includes instances of both revolution and Revolution.

Note how the count has increased nearly 30 fold for those journal article

titles that contain the keyword america. As before, cycling back and

adding > results/, followed by a filename (ideally in .txt format), will save the results to a data file.

So far we have counted strings in files and printed those counts to the shell or to

a file. But the real power of grep comes in that you can

also use it to create subsets of tabulated data (or indeed any data)

from one or multiple files.

$ grep -i revolution *.tsv

This script looks in the defined files and prints any lines containing revolution

(without regard to case) to the shell.

$ grep -i revolution *.tsv > results/2016-07-19_JAi-revolution.tsv

This saves the subsetted data to file.

However, if we look at this file, it contains every instance of the

string ‘revolution’ including as a single word and as part of other words

such as ‘revolutionary’. This perhaps isn’t as useful as we thought…

Thankfully, the -w flag instructs grep to look for whole words only,

giving us greater precision in our search.

$ grep -iw revolution *.tsv > results/DATE_JAiw-revolution.tsv

This script looks in both of the defined files and

exports any lines containing the whole word revolution (without regard to case)

to the specified .tsv file.

We can show the difference between the files we created.

$ wc -l results/*.tsv

Output:

10695 2016-07-19_JAi-revolution.tsv

7859 2016-07-19_JAw-revolution.tsv

18554 total

Finally, let’s try out using a regular expression to search for similar words.

Tip: Basic and extended regular expressions

There are unfortunately both “basic” and “extended” regular expressions. This is a common cause of confusion, since most tutorials, including ours, teach extended regular expression, but

grepuses basic by default. Unles you want to remember the details, make your life easy by always using extended regular expressions (-Eflag) when doing something more complex than searching for a plain string.

The regular expression fr[ae]nc[eh] will match “france”, “french”, but also “frence” and “franch”.

It’s generally a good idea to enclose the expression in single quotation marks, since

that ensures the shell sends it directly to grep without any processing (such as trying to

expand the wildcard operator *).

$ grep -iwE 'fr[ae]nc[eh]' *.tsv

The shell will print out each matching line.

We include the -o flag to print only the matching part of the lines e.g.

(handy for isolating/checking results):

$ grep -iwEo 'fr[ae]nc[eh]' *.tsv

Tip: Invalid option – o?

If you get an error message “invalid option – o” when running the above command, it means you use a version of

grepthat doesn’t support the-oflag. This is for instance the case with the version ofgrepthat comes with Git Bash on Windows. Since the flag is not crucial to this lesson, please just relax and ignore the problem. If you really needed the flag, however, you could have installed another version ofgrep. The situation for Windows users also improves on Windows 10 with the new Bash on Windows.

Pair up with your neighbor and work on these exercies:

Exercise 14: Case sensitive search

Search for all case sensitive instances of a word you choose in all four derived tsv files in this directory. Print your results to the shell.

Exercise 14 Solution

Exercise 15: Case sensitive search in select files

Search for all case sensitive instances of a word you choose in the ‘America’ and ‘Africa’ tsv files in this directory. Print your results to the shell.

Exercise 15 Solution

Exercise 16: Count words (case sensitive)

Count all case sensitive instances of a word you choose in the ‘America’ and ‘Africa’ tsv files in this directory. Print your results to the shell.

Exercise 16 Solution

Exercise 17: Count words (case insensitive)

Count all case insensitive instances of that word in the ‘America’ and ‘Africa’ tsv files in this directory. Print your results to the shell.

Exercise 17 Solution

Exercise 18: Case insensitive search in select files

Search for all case insensitive instances of that word in the ‘America’ and ‘Africa’ tsv files in this directory. Print your results to a file

results/new.tsv.

Exercise 18 Solution

Exercise 19: Counting number of files, part II

In the earlier counting exercise in this episode, you tried counting the number of files and directories in the current directory.

- Recall that the command

ls -l | wc -ltook us quite far, but the result was one too high because it included the “total” line in the line count.- With the knowledge of

grep, can you figure out how to exclude the “total” line from thels -loutput?- Hint: You want to exclude any line starting with the text “total”. The hat character (^) is used in regular expressions to indicate the start of a line.